Invented before the advent of digital computers, magnetic tape storage is the backbone of cold storage in enterprise data centers. Companies are competing to find ways to make tape storage denser, faster, and more searchable.

Where there’s business, there’s a need for record keeping. And where records need to be archived in bulk, there’s a need for cheap and durable media to serve cold storage needs. Thankfully, there’s an easy solution, and it’s been around for almost a century: magnetic tape.

Given the rapid development of data storage technologies over the years, magnetic storage media is something of a marvel. Companies still use tape in state-of-the-art data centers, but engineers developed the underlying tech before the advent of computers.

Who said an old dog can’t learn new tricks? Despite the age of tape storage technology, innovation continues. Companies like IBM and Western Digital are bringing tape into the future by making the media denser, faster, and more easily searchable.

Here’s a look at the past and future of magnetic tape, the venerable workhorse of cold storage.

The Sound of Storage

Originally used for audio recording, magnetic storage predates digital computers by decades. Danish scientist Valdemar Poulsen developed the earliest version, magnetic wire recording, in the late 1800s. In 1928, German engineer Fritz Pleumer created the first magnetic tape by coating strips of plastic with iron dioxide.

In the early 1950s, the very first general purpose business computer, UNIVAC I, used magnetic tape, rather than punch cards, to store programs.

IBM made further improvements, using a lighter material than UNIVAC I’s steel tape, making it easier to stop the tape at the appropriate place. The firm also found ways to start and stop rolls of tapes at high speeds, helping to quicken the read-write processes.

The basic idea of tape storage was in place early on. Ever since, firms have been competing to adjust the underlying technology in order to make tape denser, faster, and more durable.

Magnetic Tape: Just What It Sounds Like

While it’s been almost a century since the medium first appeared, magnetic tape is still made of the same basic materials. First, you take a plastic base. Manufacturers coat one side of it with a magnetic material such as iron oxide powder, together with a binding material to ensure that it properly sticks to the plastic.

Iron oxide is a ferromagnet: it can be polarized by a magnetic flux, and then retains this magnetism. This means that a write head can apply a magnetic flux to control the polarity of bits on the tape, with opposite polarities representing 0 and 1. Using magnetic polarity to represent bits is the same principle that underlies the floppy disks of yesteryear, as well as modern hard drives.

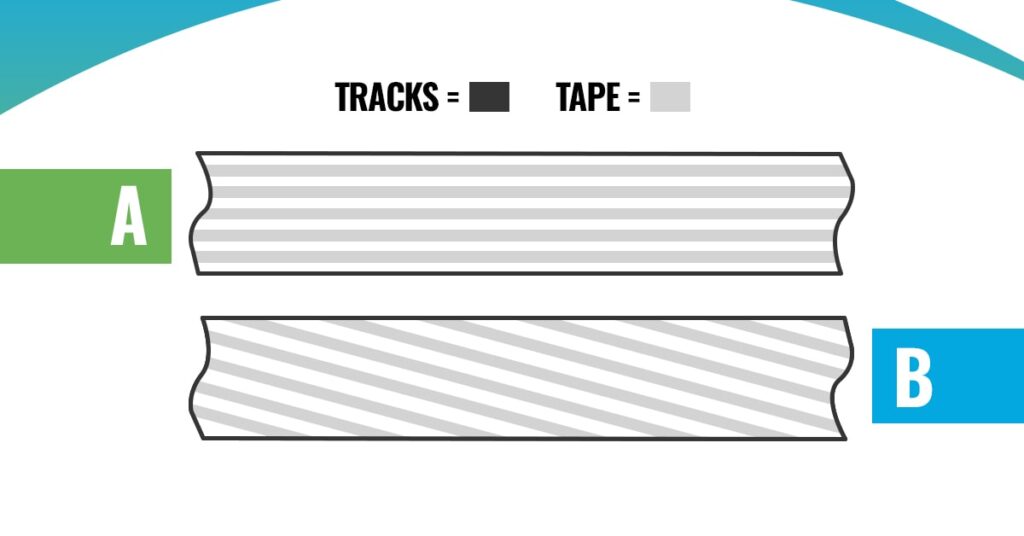

There are different ways to write data onto a tape, just as there are different ways to write to a hard drive.

Linear recording (Fig. A above) is the most mechanically straightforward method, with data striped down the length of the track. With helical recording (Fig. B above), data is striped diagonally across the width of the tape. Helical recording has higher transfer speeds and greater density, but lower reliability.

Hard drives also benefit from creative use of space. With shingled magnetic recording, HDD manufacturers achieve greater storage density by partially overlapping tracks, like shingles on a roof.

The tape is typically stored in a cartridge according to certain shared standards. Nowadays, the most common type of tape storage is Linear Tape-Open, or LTO. IBM, Hewlett Packard Enterprises, and Quantum developed LTO as an open standard in the late ’90s.

LTO uses the common ½ inch tape format, and can last for about 15-30 years. Cartridges also contain a memory chip, which is used to identify the tape within as well as information about storage use.

Strengths and Limitations of Tape Storage

There are many qualities which make tape storage an enduringly popular solution for cold storage.

One major upside is that tape is durable. It can last as long as 30 years in optimal conditions, compared to 3-5 years for HDD and 5-10 years for SSD. Another increasingly important feature of tape is the security it offers: when properly stored, there’s an air gap which makes tape less susceptible to online threats, at least until programs learn to jump. Speed is a plus as well: where large sequential reads are concerned, tape has the advantage over HDD.

The medium isn’t without its drawbacks, however. While reading a whole tape is fast, searching for and accessing a particular block can be slow. The sequential nature of tape read/write means that when accessing a specific block, the tape must physically wind all previous data blocks under the read head. For similar reasons, it’s also quite difficult to modify, recover, or replace individual files in a tape. In addition, dust, humidity, shock, and strong magnetic fields can all damage tape.

Ultimately, the most important factor in the continued use of tape is its low total cost of ownership (TCO). As measured on a cost-per-TB basis, magnetic tape has the lowest TCO of any storage medium. It’s energy efficient, is available in very high capacity, and can be quickly cooled.

Tape isn’t without its challengers. Some have begun to look into new technologies, such as DNA data storage, which promise greater density and longevity.

Continued Growth

Tape storage has long been the backbone of cold storage, and shows no signs of slowing down. Capacities are soaring, with 1TB-200TB drives projected to clinch the largest market share.

One major driver of growth has been an explosion in enterprise-grade data. As the global IoT grows and big data analytics increases in sophistication, there’s a demand for long-term solutions to store useful data at scale. Accordingly, the market for tape is projected to grow steadily at a CAGR of 8.2%, reaching a value of almost $13 billion by 2033.

Another driver in the adoption of tape is the increasing frequency of ransomware attacks. As attacks on organizational networks increase, businesses increasingly look to tape as a secure backup solution. Data is typically backed up twice, on different media, and a common strategy is to have one copy backed up to tape while cloud or disk-based solutions provide additional security.

Innovations in Tape Storage

The tape market isn’t just growing in revenue: after almost a century, it’s also still growing in sophistication, as leading manufacturers bring significant innovation to the table.

Leading the charge is LTO-9, the latest version of the LTO standard. LTO-9 boasts 400MB/second native transfer speed, which is a 25% increase compared to LTO-8, and a 1400% increase over the course of the past decade. As for capacity, LTO-9 cartridges also have a 50% boost over LTO-8, with 18TB tapes.

LTO-9 brings a powerful error correction algorithm to the table, for an error rate of 1 in 10^19. This means that if you had 130 tape drives, you would need to run them, on average, for a whole year before the algorithm lets an error slip through.

LTO-9 also features oRAO, or “Open Recommended Access Order”. This allows data centers to retrieve tape content more efficiently by cleverly arraying data on the track. Does it work? Just ask CERN, which has rolled out LTO-9 to store data generated by the Large Hadron Collider. Its tests suggest that LTO-9 allows for 30%-70% faster access to data anywhere on the tape, successfully chipping away at one of the primary drawbacks of tape storage.

Stronger With Strontium Ferrite

Fujifilm and IBM are two of the largest tape manufacturers. What happens when they join forces? 580TB tape!

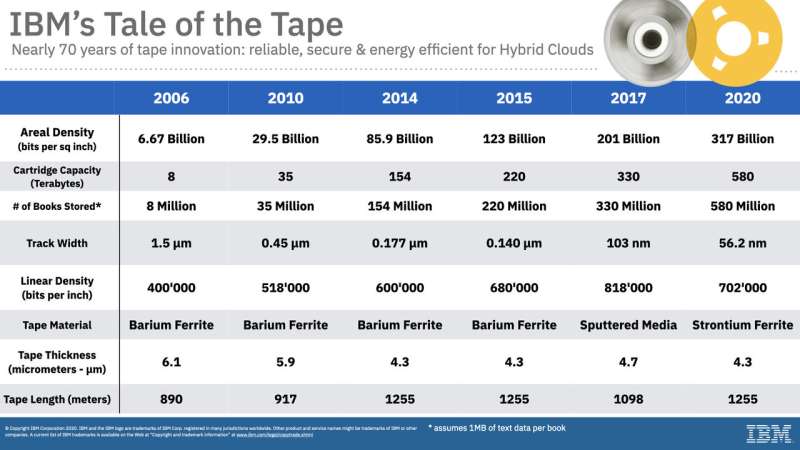

The two firms accomplished this by reducing the grain size of the magnetic material which covers the tape. While iron oxide used to be common, companies research various materials in an effort to find the best effect. Previously, the firm used barium ferrite, allowing for 220TB tape drives.

IBM and Fujifilm are now shifting to a new material known as strontium ferrite. The smaller particles allowed them to move from 123 billion bits per square inch to 317 billion bits per square inch. In addition, the new tech makes use of a low-friction tape head, allowing for extremely precise positioning. The tape passes under the read head at 15km/hr, only to come to rest with an accuracy of around 1.5 times the width of a DNA molecule.

Outside of the lab, the two firms have set records for cartridge capacity. The 50TB IBM 3592 JF tape cartridge is 2.5x the capacity of the previous record holders. The tape within uses both strontium ferrite and the more traditional barium ferrite.

Tape Dressed in HDD’s Clothing

What do you get when you cross magnetic tape with a read-write head and an HDD-style form factor? Ask Western Digital.

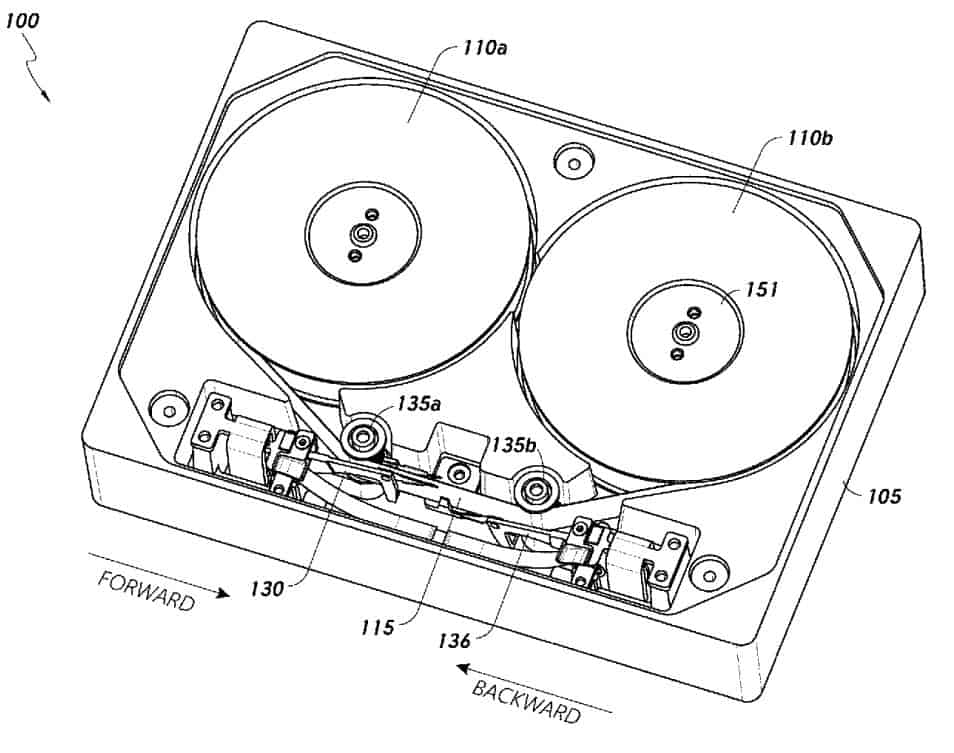

WD has taken out several patents on “tape embedded drives”. These are enclosed tape drives in which the read/write head is included within the media itself, as in an HDD. Such drives are intermediate between large but slow tapes and faster but lower capacity hard drives.

The patent suggests that these devices would have a 2.5- or 3.5-inch form factor, allowing them to be easily adopted by data centers and hyperscalers. This development could further boost demand for tape, and, if cost effective, simplify tape archival storage.

Tapping Tape’s Potential

Tape storage has come a long way since 1928, and it’s no wonder that it’s still in use. Magnetic tape is portable, the air gap makes it resistant to cyber attacks if stored properly, and it boasts a low total cost of ownership. Despite its age, tape tech hasn’t stood still, and the innovations being made now by companies like Fujifilm, IBM, and Western Digital will ensure that tape remains the backbone of cold storage for a long time to come.

Find out how Horizon can help you manage your storage hardware lifecycles to reduce total cost of ownership and green your business.