A hard drive is a valuable instrument. This is especially true of the high-cap drives that form the backbone of nearline storage. Given the expense (not to mention the precarious status of global tech supply chains), reuse is an attractive option for enterprise and hyperscalers alike.

Drive reuse helps companies extract value from aging drives, and is the front line in the perennial struggle against e-waste. However, it wasn’t always this way.

To assure purchasers of quality and sellers of data security, a lot needs to be in place. Alongside evolving techniques of circular design, there’s a whole infrastructure of norms and standards that enable the secure reuse of HDDs at scale. For instance, factory recertification has emerged as a rigorous process that allows OEMs to securely sell quality drives that have seen little-or-no use.

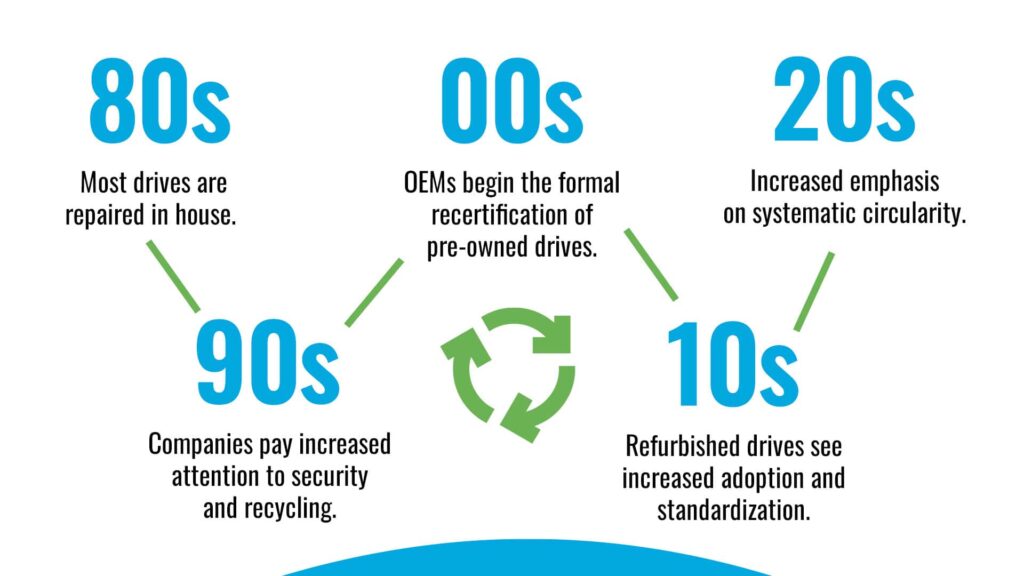

In this piece, we’ll trace the history of hard drive reuse. This will take us from the humble in-house repair that extended drive life in the ‘80s, through the growing recognition of security requirements in the ‘90s, and finally to the more intricate recertification processes used by OEMs today.

Ancient Times: The Prehistory of Reuse

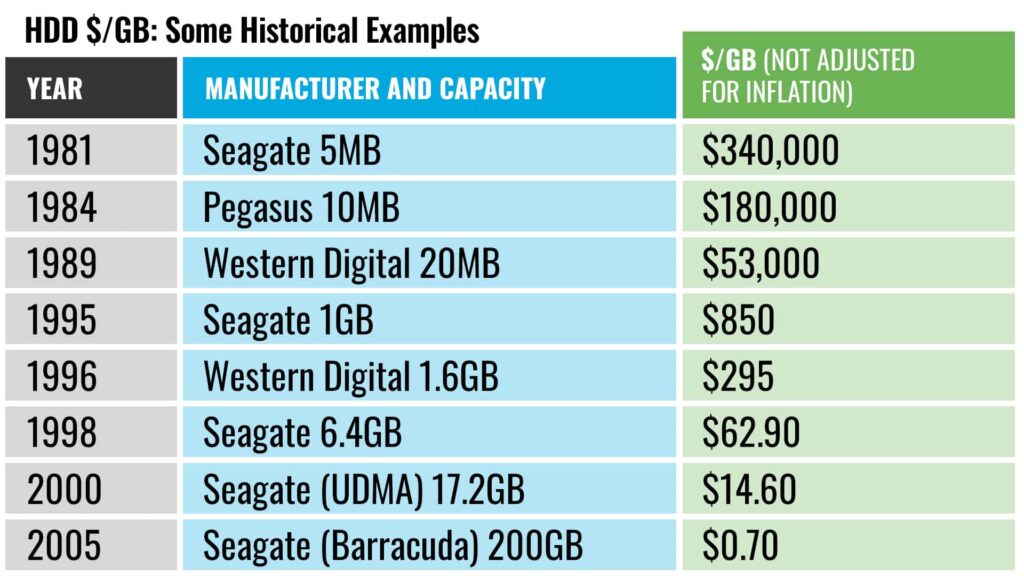

The roots of enterprise HDD are ancient indeed — at least in tech years. Way back in the 1980s, data storage was much less widespread than today. Hard drives for personal computers were only introduced in 1980. Before 1983, less than a million hard drives were shipped per year, with unit shipments ballooning to 20+ million by the end of the decade.

Hard drives were precision instruments, and often repaired in-house as a part of IT maintenance. The repair process could involve inspecting drives for visible issues like stuck spindles and arms, misaligned heads, and jammed platters. Checking for electrical, firmware, and interface issues using diagnostic tools was also routine. Repairs could range from “stiction recovery,” to replacing logic boards.

A major limitation was that dust particles can gum up HDDs, meaning that repair is often best performed in a clean room. Clean rooms are expensive and rare, limiting the capacity of most firms to do certain in-house fixes. In the 1980s, OEMs had begun to use clean rooms for manufacture, but there were not yet any structured refurbishment or recertification programs.

Related Reading

From robotic drive dismantlers to the recovery of rare metals and platter substrates, researchers have found no shortage of clever ways to extract value from aging hardware.

Early ’90s: Early Security Debates

The 90s saw a more concerted effort to think about the security implications of reuse. For example, in 1992 the National Computer Security Center issued a report on “object reuse” in relation to data security. In anticipation of now common sanitization practices, it discussed overwriting processes as well as procedures that ensured unpurged drives could not be accessed before sanitization.

In the same year, a CPA Journal article raised important questions about discarded drives:

“The simplest method to prevent such a problem is to never reuse disks, simply trash them once used. Although this would probably please the company officers in charge of security, it leaves much to be desired. With the massive emphasis on cost control in these economically tight times, this would be an unacceptable approach in most companies.” – I. Craig McKay, 1992

Here, the main concern is economic: trashing drives is a waste of money. In retrospect, we now know that once hard drives were produced on a truly massive scale, e-waste became a large issue as well. Interestingly, the article makes a distinction between mere deletion and genuine erasure, though it does not put it in these terms.

Related Reading

By addressing security concerns, rigorous standards for data sanitization play an important role in encouraging drive reuse.

Late ’90s: Recycling & Warranties

In the late ‘90s, structured recertification processes were introduced alongside manufacturer-backed warranties. Companies like IBM and Seagate began implementing structured procedures: cleaning, replacing failed components, and full factory testing. Drives were “certified” and resold, often with warranty support. This shift marked the beginning of what we now call factory recertification.

For example, by 1997, Seagate was offering repair services, and confident enough in their overall process to offer a warranty “for one year or the balance of your original warranty, whichever is greater.”

The late ‘90s also saw initial interest in systematic circularity and reuse policies. A 1997 EPA report, “Extended Product Responsibility: A New Principle for Product-Oriented Pollution Prevention,” contained a long section on the electronics industry, with case studies. For example, the Hardware Resource Organization (HRO), part of Hewlett-Packard, served as a refurbishment center, as well as a recycling hub. It saw 18% resale of components such as disk drives.

Related Reading

Over time, the storage industry has shifted from one-off, in-house repairs to intricate OEM-approved processes for vetting and reselling drives.

2000s: OEM Expansion

In the 2000s, Seagate, WD, Hitachi, and Toshiba expanded certified drive offerings:

- Seagate offered “Certified Pre-Owned” drives, including enterprise-grade models, which were tested and warrantied.

- Western Digital sold recertified versions of WD Red (NAS) and WD Gold (enterprise) drives.

- Hitachi (prior to its 2012 acquisition by WD) also focused on refurbishing enterprise drives.

- In 2009, Toshiba launched the Toshiba Assurance Refurbishment Program, targeting consumer and enterprise markets.

As OEM refurbishment programs hit their stride, third-party refurbishers also emerged as key players. OEMs began establishing business relationships with such refurbishers, providing another outlet for reuse.

Sustainability Awareness

The ‘00s also saw an increased emphasis on sustainability. Seagate’s Global Annual Citizenship reports, available back to 2005, provide an interesting case study.

Seagate’s 2005 report emphasized reuse of surplus equipment or its components as part of its “Seagate Surplus Asset Policy.”

“By Seagate Surplus Asset policy, a priority is to reuse surplus equipment for its original intended purpose. When that is not possible, reuse of components from the equipment is emphasized, followed by recovery of materials and substances (such as precious metals) from the equipment.” – FY2005 Global Annual Citizenship Report.

The 2009 report outlined Seagate’s “Drive for Education,” which put “much-needed storage into local schools while also doing Mother Earth a favor by keeping the drives out of the e-waste stream.” By 2011, Seagate was going beyond reuse to address circular design, increasing recyclable content to 90% of the weight of its products.

Related Reading

Whether you’re a hyperscaler or a small enterprise, reducing e-waste involves having a well thought-out lifecycle strategy for your storage devices.

Is Less More? Hard Drive Procurement and the Waste Hierarchy

2010s & Early 2020s: Mainstream Adoption

By the 2010s, refurbished drives began to see mainstream adoption, becoming more commonplace across consumer and enterprise markets. Due to the increased rigor of the testing process, there was a growing acceptance of recertified drives for business applications, especially in backup, archival, and NAS environments.

Just ask Horizon Technology’s COO Stephen Buckler. “Factory recertified hard drives have more than demonstrated that they offer real quality”, he explains. “For the right use cases, recertified drives deliver the perfect balance between cost and performance.”

Another perk of recertified drives is that they can help fill the gap in the event of a drive shortfall. For example, the hard drive industry was deeply shaken back in 2011 when severe flooding in Thailand led to the closure of almost 200 factories.

As a result, Western Digital saw a 51% q-o-q decline, and Nidec, which manufactures HDD motors, was also affected. Companies such as Backblaze began “drive farming”, handling the shortfall by recruiting employees, friends, and family to buy up cheap 3TB drives from Costco and Best Buy.

While precise figures are hard to come by, it stands to reason that such shortages and price spikes made sources of quality recertified drives look quite attractive.

The 2020s saw the release of the IEEE 2883 standards for storage sanitization. This is a big enabler of reuse, since security concerns are the primary reason many firms opt for drive destruction over reuse or recycling. The new standards outline acceptable methods for “purging” data, rendering that data inaccessible to even advanced bad actors who are able to access parts of the drive not visible to the host.

Related Reading

Factory recertified drives are rigorously vetted and typically available at a reduced cost-per-terabyte. For the right use cases, recertified inventory can reduce data center storage costs.

Factory Recertified Drives & The Case for Sustainable Storage

2020s and Beyond: Circularity & CDI Grading

It’s one thing to value circularity, and another to approach it systematically.

You can see this in Seagate’s 2020 Global Citizenship report. In addition to the expected emphasis on reuse and repair, the report now emphasizes the importance of a secure chain of custody in order to avoid bad actors from accessing data from products slated for reuse. Drive reuse runs on trust, and maintaining that trust requires that the parties concerned to dot their i’s and cross their t’s.

To foster collaboration on sustainable data storage, the Circular Drive Initiative (CDI) was created to encourage circular design and reuse. Giving companies a sense of appropriate use cases is one way to encourage drive reuse, and to this end CDI is working on a drive grading system to categorize reusable drives. Grade A drives are appropriate for high-sensitivity use cases such as finance and health care, whereas grade B drives are appropriate for most other enterprise tasks.

Related Reading

A 2024 study revealed a huge gap between drives eligible for reuse and those that actually go on to a second life.

A Process You Can Count On

Storage owners have been thinking about hard drive reuse and repair for as long as the medium has been around. However, as hard drives have become more central to the increasingly important global data infrastructure, trust is now the main barrier to reuse at scale. Purchasers want to know that recertified and reused drives are reliable, and owners of aging drives need to be confident data won’t leak before they opt for reuse over destruction.

Building trust requires airtight processes, rather than new technology. As reuse has become more important, robust procedures for ensuring product quality have grown in sophistication. From the initial repair warranties in the 90s to the standard-driven sanitization and recertification procedures in play today, a great deal of thought has gone into fostering the trust that makes the resale market work. The result: when properly vetted, reused drives are now better, and safer, than ever before.

Horizon is a Seagate authorized seller of factory recertified hard drives. Get in touch to find out how our recertified drives can reduce the total cost of ownership of your storage hardware.